For breakfast the next morning, Dorothea again ordered graviéra cheese, which was served with olives this time, and orange juice. I had a feta omelet cooked in olive oil, and drank Europe’s universal instant coffee, Nescafe. Afterwards we once again shared toast and jam with the local corps of wasps and flies, peacefully or at least non-violently.

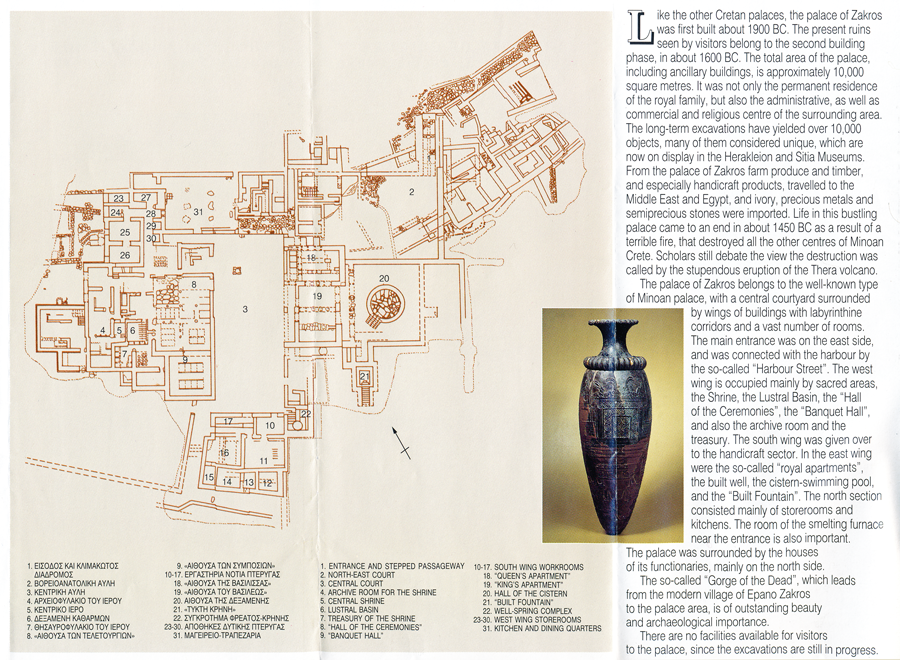

After breakfast we read for a while and then set out to see the ruins of the Minoan palace. It wasn’t a guided tour, so we had only a leaflet they gave us at the ticket window to tell us what everything was. (Or at least, what the archaeologists think everything was.) I’ve reproduced the part with the map at the right.)

Káto Zákros was the last major palace to be discovered, in the early 1960s. A British team had done some digging there around the turn of the 20th century, but found only a couple of houses before giving up. A Greek archaologist, Nikólaos Pláton, dug just a few yards beyond the point where the Brits had left off, and almost immediately found the fourth of Minoan Crete’s big palaces. “The site yielded up an enormous quantity of treasures and everyday items,” according to the Rough Guide, mainly for two reasons: the careful methods of modern archaeological excavation, and the fact that the palace had been forgotten so long ago that nobody had gotten around to looting it.

The treasures and everyday items are gone from the site now, of course, on display in various museums in Crete and the rest of Greece. We would catch up with some of them a few days later in Sitía. What there was to see on the site was an often baffling arrangement of stones that defined the ground plan of the palace and part of the town outside it. Further excavation is unlikely, because (as the Rough Guide puts it plainly) “this end of the island [i.e., Crete] is gradually sinking.”

Káto Zákros was the last major palace to be discovered, in the early 1960s. A British team had done some digging there around the turn of the 20th century, but found only a couple of houses before giving up. A Greek archaologist, Nikólaos Pláton, dug just a few yards beyond the point where the Brits had left off, and almost immediately found the fourth of Minoan Crete’s big palaces. “The site yielded up an enormous quantity of treasures and everyday items,” according to the Rough Guide, mainly for two reasons: the careful methods of modern archaeological excavation, and the fact that the palace had been forgotten so long ago that nobody had gotten around to looting it.

The treasures and everyday items are gone from the site now, of course, on display in various museums in Crete and the rest of Greece. We would catch up with some of them a few days later in Sitía. What there was to see on the site was an often baffling arrangement of stones that defined the ground plan of the palace and part of the town outside it. Further excavation is unlikely, because (as the Rough Guide puts it plainly) “this end of the island [i.e., Crete] is gradually sinking.”

A rising water table has filled some of the lower parts, like this cistern, with water. All the guidebooks and websites mention the turtles that now live there—it sounds as if the place was running over with them, but this is the only one we saw. There may be more turtles around in the spring, before the long, dry summer sets in.

Eastern Crete’s subsidence into the sea is gradual enough that we didn’t feel personally threatened by it, and I’m sure that the Akrogiáli Tavérna will be there to support Níkos and his descendants for several more generations, but the process has been going on for a long time, long enough to make the palace of Káto Zákros look like an exception to the Minoan policy of building palaces far enough from the sea to avoid leading seaborne raiders into temptation. But it’s generally agreed that, back around 1900 BCE when it was built, this palace was a good deal farther from the shore than it is now.

Eastern Crete’s subsidence into the sea is gradual enough that we didn’t feel personally threatened by it, and I’m sure that the Akrogiáli Tavérna will be there to support Níkos and his descendants for several more generations, but the process has been going on for a long time, long enough to make the palace of Káto Zákros look like an exception to the Minoan policy of building palaces far enough from the sea to avoid leading seaborne raiders into temptation. But it’s generally agreed that, back around 1900 BCE when it was built, this palace was a good deal farther from the shore than it is now.

This picture shows what is believed to be the road that led from the palace to the seaport that must have been served it. Káto Zákros’ position at the eastern extremity of Crete was advantageous for trade with Egypt and the developed countries of the Fertile Crescent. (The archaeologists found an elephant tusk as well as some pottery items from Ugarit—a small kingdom on what's now the north coast of Syria.) There’s little chance that any of the port will be dug up; it must lie well out under the water whose gentle lapping provided background music for our meals.

(The telephone pole in the picture is thought to be a later addition.)

(The telephone pole in the picture is thought to be a later addition.)

There were few other visitors, and the peaceful quiet of the site and the landscape around it had a good deal of nonacademic charm. In the distant background of this picture you can see the mouth of the Gorge of the Dead. The Minoan burials in caves on the gorge’s steep sides were, according to some accounts I’ve seen, a comparatively recent discovery, though I haven’t been able to find out exactly when they were discovered or how long the gorge has had its present name.

We were back at the Coral Rooms before 1:00. Dorothea lay down while I read for a while, and we went down for lunch at 2:00. Dorothea saw the Dutch couple from next door to us taking each other’s picture, and volunteered to take one of the two of them. The four of us wound up sharing a table, though they were finishing their meal and we were just starting ours. We sat together until about 4:45, by Dorothea’s reckoning, talking “about traffic patterns in different parts of the world, the economy, jazz, Cretan music, languages, the banjo, etc.”

Of course, we did more than just talk for almost three hours—Dorothea and I also ordered and ate our lunch. We shared dákos (under its imposing local name, koupoukópsomo), and while Dorothea had ratatouille with potatoes, I had yiouvétsi, a dish involving lamb stewed with orzo, those little rice-shaped bits of pasta. Greeks sometimes use that Italian name, but also call them manéstra or kritharáki. (The second Greek word means ‘little barley.’) A half-liter of white wine also vanished during the conversation.

Back on the terrace, we buried our noses in our books until 7:30. (A doubly figurative expression, as [1] we were both reading electronic devices rather than books, and [2] reading a book is impossible if the reader literally inserts his or her nose between the pages. Try it if you don’t believe me.)

We also met the people who had replaced the Swiss couple in the room on the other side of ours. Both husband and wife are natives of New Zealand, but they’d lived in Sitía for the previous three years. They often come to Káto Zákros for the weekend, they told us, as they were doing now, and are on such good terms with Níkos that he has sometimes let them come down out of season, when no one else is there; he gives them a key.

We were back at the Coral Rooms before 1:00. Dorothea lay down while I read for a while, and we went down for lunch at 2:00. Dorothea saw the Dutch couple from next door to us taking each other’s picture, and volunteered to take one of the two of them. The four of us wound up sharing a table, though they were finishing their meal and we were just starting ours. We sat together until about 4:45, by Dorothea’s reckoning, talking “about traffic patterns in different parts of the world, the economy, jazz, Cretan music, languages, the banjo, etc.”

Of course, we did more than just talk for almost three hours—Dorothea and I also ordered and ate our lunch. We shared dákos (under its imposing local name, koupoukópsomo), and while Dorothea had ratatouille with potatoes, I had yiouvétsi, a dish involving lamb stewed with orzo, those little rice-shaped bits of pasta. Greeks sometimes use that Italian name, but also call them manéstra or kritharáki. (The second Greek word means ‘little barley.’) A half-liter of white wine also vanished during the conversation.

Back on the terrace, we buried our noses in our books until 7:30. (A doubly figurative expression, as [1] we were both reading electronic devices rather than books, and [2] reading a book is impossible if the reader literally inserts his or her nose between the pages. Try it if you don’t believe me.)

We also met the people who had replaced the Swiss couple in the room on the other side of ours. Both husband and wife are natives of New Zealand, but they’d lived in Sitía for the previous three years. They often come to Káto Zákros for the weekend, they told us, as they were doing now, and are on such good terms with Níkos that he has sometimes let them come down out of season, when no one else is there; he gives them a key.

Our punishing schedule now required us to eat another meal, our last dinner at the Akrogiáli tavérna. The tamarisk trees sprinkled their little white flowers on us, just like on our terrace, while we sat at our table eating pork souvláki (Dorothea), moussaká (me), and a shared dish of hórta, with a half-liter of retsina.

Níkos phoned Yiánni, who was coming the next day to pick us up, to ask him to bring cigarettes. The tiny beach settlement has no establishment where such things can be purchased, and having Yiánni bring him the cigarettes saved Níkos an eleven-mile round trip.

Níkos phoned Yiánni, who was coming the next day to pick us up, to ask him to bring cigarettes. The tiny beach settlement has no establishment where such things can be purchased, and having Yiánni bring him the cigarettes saved Níkos an eleven-mile round trip.